Carmabi has noticed ‘coral bleaching’ around Curaçao; so far, damage is not too bad

Carmabi, Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance (DCNA)Since 1955, Carmabi has been monitoring and conducting research on the coral reefs around Curaçao. With the water temperature now dropping, it seems that the corals have weathered this period, with warmer water than normal, well. This positive development marks a notable contrast to previous years where 'coral bleaching' was a concern for Curaçao, as well as when comparing local reefs to others in the Caribbean.

Due to El Niño and ongoing climate change, seawater in the Caribbean is this year warmer than ever before. In fact, for Curacao, the seawater has never been as warm as it’s been for the past 3 months, with temperatures reaching 31 degrees in October. Temperatures have also been very hot on land, a complaint made by many people over the recent months. Persistent heat, such as we’ve experienced this year, is not only a problem for people. Other animals can also suffer from higher than normal temperatures. Corals are a good example of this.

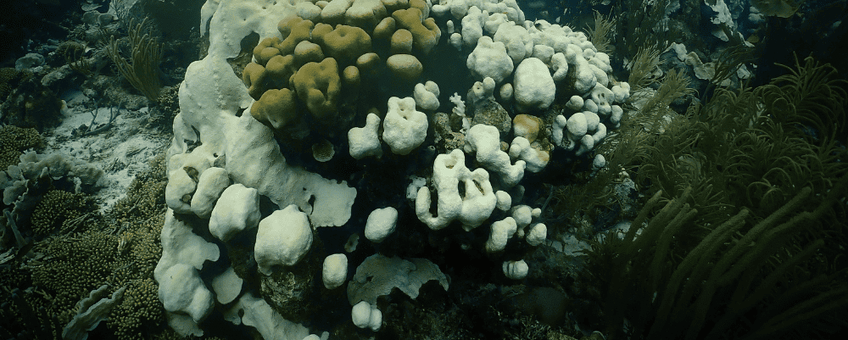

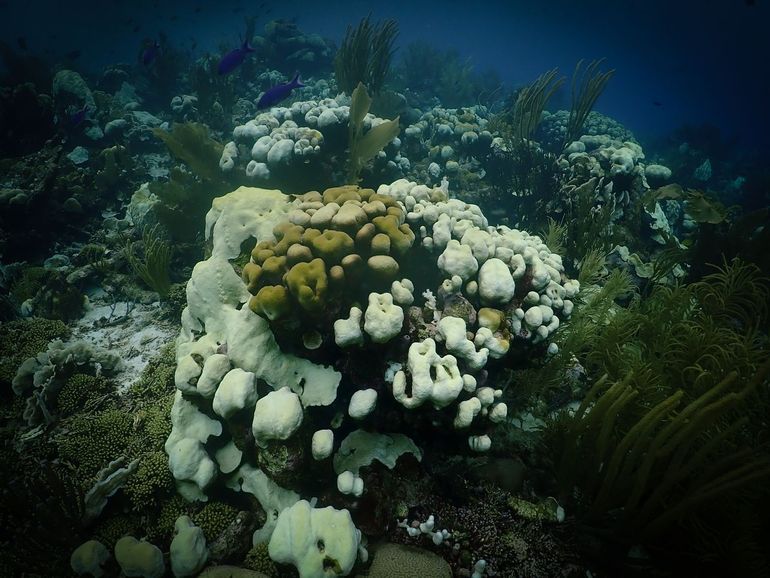

Microscopic algae found in the tissue of reef-building corals normally provide their host (the coral) with food through photosynthesis, but begin to produce toxins when seawater warms above 29 degrees. Corals then release these algae into the surrounding water. Since these algae give corals their typical green/brown color, corals appear to bleach when the algae are emitted. The coral tissue itself is transparent, making the underlying white coral skeleton visible. That is why this phenomenon is called ‘coral bleaching’.

If the seawater cools down enough after a few weeks, the algae return to the coral and everything is just like before. However, if the seawater remains warm for too long, some coral species may starve because they depend on these algae for their food supply. When the water stays warm for too long, as it did this year, many coral colonies start to die from starvation after a month. How warm the seawater becomes and how long it remains above 29 degrees ultimately determines how many corals will die due to ‘bleaching’.

In 1998, 2005 and 2010 the seawater was also very warm, although not as warm as this year. In some places in the Caribbean, 80 percent of all coral colonies bleached in these years and up to 60 percent died locally. 'Coral bleaching' is therefore often seen as one of the most important phenomena that contributes to the decline of coral reefs worldwide. However, ‘coral bleaching’ is not something that can be combated. It is a symptom of an underlying problem, namely the increasingly warmer sea caused by excessive CO2 emissions.

This year, between August and November, the seawater around Curaçao was warmer than 29 degrees (for the first time) for 16 weeks and in some Caribbean locations (for example the Florida Keys) the mortality of corals is enormous. Somewhat to the surprise of coral researchers, so far, the damage around Curaçao appears to not be too bad. Many corals are currently bleached, but many species are largely still alive, despite the historically long period of excessively high seawater temperatures, and in contrast to previous 'bleaching events' on the island. Because the seawater is currently dropping below 29 degrees again, there is hope that many of the corals that are currently still bleached will soon reabsorb their algae from the surrounding water and the previously expected mass mortality will not occur. The reason for this is currently unknown, but it is suspected that some corals may be slowly adapting to the warming water or have switched to other food sources, such as plankton. Only in a month or so will it become clear whether the now bleached corals on Curaçao will ultimately survive or whether the damage suffered is already so great that many colonies will die in the near future.

In the coming period, Carmabi will pay close attention to this phenomenon through various channels. The research institute that falls under Carmabi will continue to monitor the situation and will experiment with options to restore the coral reef, with its own researchers and guest researchers.

Carmabi emphasizes the crucial role of such research in understanding and conserving coral reef biodiversity. Monitoring these events helps to develop effective strategies for the conservation of this precious ecosystem. The foundation remains committed to the protection and sustainable management of biodiversity around Curaçao, in light of future challenges and conservation needs for the region’s unique marine life.

More information

- See Calacademy.org/educators/why-do-corals-bleach for a video explaining the process of 'coral bleaching' by scientists from the California Academy of Sciences who studied this phenomenon in Curaçao.