Three Caribbean heart cockles new to science, also occurring on the ABC islands

ANEMOON FoundationHeart cockles are bivalve molluscs with ribs radiating from the apex. Worldwide, there are about 300 species. Well-known species include the prickly cockle, sometimes washed-up on Dutch beaches and the common cockle living in large numbers in the Wadden Sea and the Dutch province of Zeeland. But not all species belonging to the family Cardiidae are 'cockles', and some species have less distinct or barely visible ribs. In English, the much smoother cockles are called egg cockles. A well-known representative is the Norwegian egg cockle (Laevicardium crassum), which also lives in the Dutch North Sea. The three newly discovered Caribbean species also belong to this group.

New to science

Jan Johan ter Poorten made his discoveries while examining material from the MNHN, the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, as part of his global research on cardiid species. This French institute collected a large amount of material during four expeditions in the Caribbean. The results of his research, including the three new species, were recently published. In this paper, the new species each received their own scientific name, thereby gaining worldwide recognition as a distinct species. What stands out is that these species remained unnoticed for so long. How is that possible? And how do you know they are new to science?

Overlooked

The French expeditions took place about 10 to 15 years ago around the Caribbean islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe and of French Guiana. Such campaigns use many techniques. In addition to hand collecting in the intertidal zone, many dives are made, dredging is carried out, traps are set, coral is brushed, and small material is suctioned from crevices between vegetation using special vacuum devices. The four expeditions yielded more than 1,000 collection points ('stations'), from depths between 0 and 600 meters. Sorting and grouping the material by family and station number is already a massive task. Then comes the main job: identification. For this, material per family is loaned to specialists. Ter Poorten is one of them. Asked why these species had never been discovered and described before, he answers: “Very briefly? They are relatively small and have long been regarded as juveniles of larger species. Basically, they were always overlooked.”

Challenge

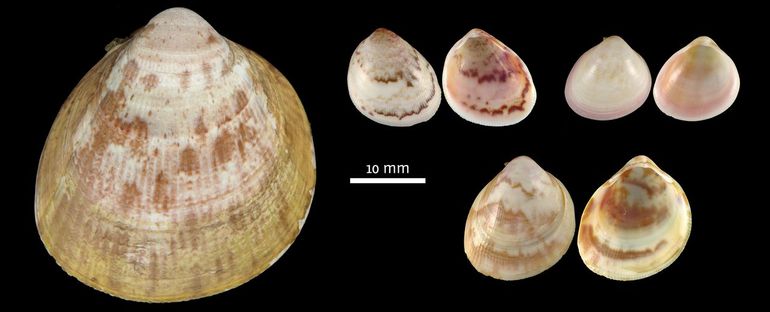

Assessing whether a species is genuinely new to science presents a major challenge and requires a lot of study, knowledge, and time. In this case, it involved months of research on 3,400 shells, representing 18 cardiid species from about 850 stations. But not all species are the same: species with distinct ribs often have clear identification features, such as scales, nodules, or spines. But species with an almost smooth surface? Ter Poorten explains: “Because of the careful collecting methods, everything was perfectly preserved. Under the microscope, additional details emerge that can sometimes be decisive for identification.” He explains how he was able to reconstruct and follow the growth development of a shell species at all stages. Illustrating with his fingers: “From such a tiny shell of just a few millimeters to an adult specimen.” Ultimately, in addition to limited supplementary DNA data, differences in microsculpture, shell thickness, and shape proved decisive. In this way, he discovered two new cockles, which he has now described as Laevicardium caribbaeum and Laevicardium solidum.

Third species

The cockle specialist explains that after extensive literature research and examining many shells in collections, something still nagged at him: “Is the puzzle now complete, or are there still pieces missing? In other words, is there a third undescribed small species involved?” To resolve this, cardiid shells were borrowed from the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt am Main, and Caribbean material from the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden was also studied. The German institute turned out to possess many cockles from Colombia, collected in the 1970s by a German-French scientist. Partly based on this material, Ter Poorten was able to confirm the presence of a third new small species. This one is slightly more inflated and somewhat more triangular in shape and was therefore described as Laevicardium globotriangulare.

Dutch and English names

Although only the scientific name is the truly correct one, for various reasons vernacular names are also in use. In the Netherlands, for example, all molluscs have Dutch names. For the three new cockles, the following names are proposed:

- Laevicardium caribbaeum: Caribbean egg cockle (Dutch: Caribische hartschelp)

- Laevicardium solidum: Solid egg cockle (Dutch: Stevige hartschelp)

- Laevicardium globotriangulare: Tumid egg cockle (Dutch: Gezwollen hartschelp)

Dutch connection

All three new species turned out to already be present in the Naturalis collection. They had often been collected decades ago in the Caribbean, including on beaches and in shallow waters around the ABC islands and the islands that are now known as the Caribbean Netherlands. The Caribbean egg cockle is found around Curaçao and Aruba. The Solid egg cockle around Curaçao, Aruba, Sint Eustatius, and Saba. The Tumid egg cockle is known from Curaçao. The species are not rare. The animals live shallowly buried in the substrate, with the short inhalant and exhalant siphons protruding at the top (see photo below). Undoubtedly, they will be found in more places in the Caribbean in the future. As will other new (cardiid) species. Ter Poorten is author of a seminal, comprehensive reference work on Cardiidae (600 pages, published in 2024). The three new species were not included, but will be in a next edition. He states: "Ultimately, the adage applies: the better you look, the more you see – even when it comes to small, smoother cockles."

Text: Rykel de Bruyne and Adriaan Gmelig Meyling, Stichting ANEMOON

Images: Jan Johan ter Poorten, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago; Philippe Maestrati, MNHN, Paris; Jerry Gagne, FMNH, Chicago